In 1603 the play Troilus and Cressida was mysteriously “blocked” from publication by James Roberts, who had issued a number of other Shakespeare quartos. And after the publication of Hamlet in 1604, no more yet-unpublished Shakespeare plays came into print (until the First Folio in 1623 added eighteen more plays), at least not from the hands of those who possessed most of them. It was as if the author had died.

The Historie of Troylus and Cressida finally appeared in quarto six years later, in 1609. Midway through its printing, however, the cover page was altered; and also, the book now contained a sharp, angry warning that other yet-unpublished Shakespeare works were in danger of being suppressed by “the grand possessors” of them. The remarkable epistle began with this heading: A NEVER WRITER TO AN EVER READER – NEWS

====================

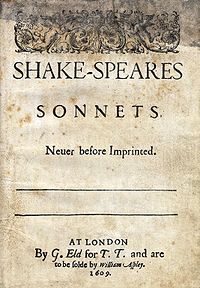

In the same year Pericles was issued, again in defiance of the unnamed “grand possessors.” Also SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS Never before Imprinted was published in 1609, only to disappear for more than a century until 1711. Inside was a strange dedication referring to the author as:

OUR EVER-LIVING POET

Calling someone “ever-living” meant the person was no longer walking around on Earth. This was 1609 and the poet of the Sonnets was “ever-living” or dead (although the Stratford man, who would get credit for the works in the future, remained alive until 1616).

You might say these uses of NEVER and EVER are, at the least, intriguing … no orthodox scholar has been able to explain them … but surely the two words were inserted consciously and deliberately:

NEVER WRITER … EVER READER … EVER-LIVING POET … [And maybe should throw in NEVER BEFORE IMPRINTED]

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, had died at fifty-four on June 24, 1604. In his body of youthful, signed poetry that he left behind, there is an “echo” poem in which the “fair young lady … clad all in color of a nun, and covered with a veil,” cries out her questions and receives answers from the echo. She plays upon “ever” for E. Ver and as an anagram of Vere; and the Echo replies with that name (my emphases added):

Oh heavens! Who was the first that bred in me this fever? Vere.

Who was the first that gave the wound whose fear I wear for ever? Vere.

What tyrant, Cupid, to my harm usurps thy golden quiver? Vere.

What wight first caught this heart and can from bondage it deliver? Vere.

So it’s beyond doubt that Edward de Vere used “ever” and variations of it in relation to his own name. In 1575 he inscribed a Latin poem on a blank page of a Greek New Testament sent to his wife, Anne Cecil, while he was away in Europe; and in one line, translated into English, he wrote that he hoped her motto would be EVER LOVER OF THE TRUTH/VERE.

In 1598 the satirist and playwright John Marston wrote the following lines (with my emphases added):

Fly far thy fame,

Most, most of me beloved! whose silent name

One letter bounds. Thy TRUE judicial style

I EVER honour; and if my love beguile

Not much my hopes, then thy unvalued worth

Shall mount fair place when Apes are turned forth.

If Edward de Vere was “Shakespeare,” it follows that his own name was “silent”; and, of course, “Edward de Vere” is bounded by one letter … E.

Also in 1598 the poet Richard Barnfield wrote a verse in which he speaks directly to “Shakespeare thou, whose honey-flowing vein (pleasing the world) thy praises doth obtaine” (again with my emphases):

Live EVER you, at least in Fame live EVER:

Well may the Body die, but Fame dies NEVER.

Clearly for certain members of society, notably writers, the issue of the great author’s actual “name” was already in play; and it appears that these folks already knew that EVER and NEVER could be used to identify him (silently) as Edward de Vere. Wits Recreation of 1640 contained an anonymous epigram that began:

To Mr. William Shake-spear

Shake-speare, we must be silent in thy praise…

Venus and Adonis appeared in 1593 with the name “William Shakespeare” printed for the first time (on the dedication to the Earl of Southampton); and Lucrece was published in 1594 with another dedication by Shakespeare to the young earl. Also in that same year, the poetical work Willobie His Avisa was published. This enigmatic work has been attributed to Edward de Vere by the highly respected Oxfordian researcher Barb Flues, through stylistic tests; and in fact it contained the first reference to “Shakespeare” other than his printed signature:

Yet Tarquyne pluckt his glistering grape,

And Shake-speare, paints poore Lucrece rape.

[I would note first the hyphenation “Shake-speare,” indicating the likelihood of a pen name. Also I would note the mention of Shakespeare in connection with his Lucrece, which was being issued simultaneously. Who else, at that time, would know about the second Shakespeare poem but the author himself?]

Willobie His Avisa winds up with a long poem The Praise of a Contented Mind, containing a passage about the historical Troilus and Cressida; and at the end of the poem, concluding Willobie itself, is the author’s printed signature in large italicized typeface:

Ever or Never

In Hamlet it seems we can hear the author’s own voice in many of the Prince’s speeches; and at the end of the first act are these famous lines with “ever” and “I” spoken together (with my emphases):

The time is out of joint. O cursed spite

That EVER I was born to set it right!

In two scenes of the play the Prince uses “ever” in connection with his “name.” Both involve Horatio, the character that Oxfordians feel is based on Edward de Vere’s cousin Horatio Vere:

Hamlet: I am glad to see you well. Horatio – or I do forget myself!

Horatio: The same, my lord, and your poor servant EVER.

Hamlet: Sir, my good friend – I’ll change THAT NAME with you. (1.2.168-70)

At the end of the full text of the play, printed in 1604 after Oxford’s death that year, the words “ever” and “name” again appear with Horatio involved, as the dying Hamlet tells him:

O good Horatio, what a WOUNDED NAME!

(Things standing thus unknown) shall live behind me!

If thou didst EVER hold me in thy heart,

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain

To tell my story. (5.2.367-71)

It’s in the Sonnets where, in my view, Oxford speaks not through a character but, rather, in his own words; and here the signature words EVER and NEVER are difficult to avoid (with my emphases):

Why write I still all one, EVER the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed,

That EVERY WORD doth ALMOST TELL MY NAME ,

Showing their birth, and where they did proceed? (76)

And in Sonnet 116 the words appear to be an insistent identification; first, speaking of love:

O no, it is an EVER-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests and is NEVER shaken…

And in the concluding couplet:

If this be error and upon me proved,

I NEVER writ, nor no man EVER loved.

Once again, of course, none of this proves that Oxford was OUR EVER-LIVING POET, but it certainly adds to the evidence. And I offer it here as No. 63 of 100 reasons to believe he was the NEVER WRITER (never acknowledged as the great author) addressing the EVER READER (those of us who have been thrilled and moved, to hilarity and tears, by his words).

TO BE CONTINUED — With a post about Oxford as “Ever or Never” in A Hundredth Sundry Flowres of 1573.

Line 7 of Sonnet 76 is quoted in Reason 63 as it is usually transcribed in modern texts – “ That every word doth almost tell my name”.

In the original printing, the word “tell” is actually printed with a first letter “s” and without the last “l” (see the word “still” in lines 5 and 10 for the difference between the contemporary printing of “s” and ”t”) so that it reads in the original text as “sel”. It seems that the typesetter misprinted the word, in which case might it have been “spel” rather than “tel” in the original manuscript ? Thus:

That EVERY word doth almost SPELL my name ?

Either way, as you observe, Sonnet 76 is another example of our never writer teling (or almost speling) his name.

Peter Willcox

Peter, it’s a good observation. Editor Steven Booth thinks it’s actually “fel” with an f, but I see no real difference between the f and the similarly designed s. [The printer spells “s” in two different ways.] It would seem that “fel” makes no sense at all, while your suggestion is very plausible, even likely. Thanks.

Whittemore, isn’t curious that the “Never writter to a ever” edition of T&C is in the same play that Troilus says “Nothing TRUER than Troilus”, proving that he himself was Troilus?

Yes, it’s curious and more than that. Troilus and Pericles were “hot” plays, for different reasons. One reason Troilus was dangerous was, as you say, Oxford virtually identifies himself through Troilus in relation to Elizabeth as Cressida.

This was the first play to be published and/or performed after Elizabeth I’s death painting her affair with Oxford but with more disdain to her than in other plays like “Two Gentlemen of Verona” (Silvia), “The Merchant of Venice” (Portia) and “Romeo and Juliet” (Rosalind), for example. Gertrude, Cressida, Cleopatra are proofs of my thought. The greedy, lustful and false Elizabeth that hid herself in her bed with her lovers is not the same fair and virtuous Elizabeth of Shakespeare’s Plays pre-1603. Looks like only after Elizabeth’s death and Oxford disapparence the truth started to be told.

Hi Hank, Hi Peter,

it’s very interesting an explanation. Yet, with due respect I’m not convinced 🙂 For me it’s a bit ‘too much’ to make a fel – spell change. Obviously there ARE mistakes in the text of the quarto, but this one would be too much, I guess. Of course I should come up with a plausible explanation of my own, for me to gain some credit, in this respect. Let me show you what I’ve found.

What if the word Oxford intended to write IS fel(l)? Then there should be a meaning of fell, not so obvious, but logical to be seen as the real meaning in the context of the sonnet-lines. And I’ve found a meaning of fell, as weaving clothes together. Look at the link below:

http://www.sewneau.com/how.to/flat.felled.seam.html

In the light of this meaning, the line

‘That every word doth almost fell my name’

would mean, that the words of the sonnets together weave as a piece of cloth, and (almost) set forth my name:

‘Showing their birth and where they did proceed’

The word ‘show’ is also more logical in this meaning (as the woven cloth with Oxford’s name would be visible, rather than audible – tell / spell).

Oops 🙂 In the previous line:

‘And keep invention in a noted weed’

if we see ‘weed’ as cloth, then the idea mentioned above is even more plausible. The ‘noted weed’, that is the cloth, woven /fell together (by my words of the sonnets), almost noted with my name.

Now I’ve looked up weed (just to be a bit more sure :)) in my great net vocabulary, and I’ve found:

‘weed: Shakes. cloth’

So seemingly Oxford did use the word weed in the meaning of cloth.

Very interesting. I have always expressed it as “noted weed” = “familiar costume [of poetry]”

Interesting about fell = weaving

Well, I can’t be sure that at Oxford’s time it was known. But at the link below there IS by the Etymologies part:

‘…Middle English fel, …’ so maybe yes, and then even we don’t need the second ‘l’-letter…

http://www.wordnik.com/words/fell

Perhaps it’s far-fetched, but nonetheless in itself I find it coherent.

And if nothing else, then a good mind-game 🙂

Again, what makes me actually ponder is, that in this very ‘central’ sonnet, in which he did hide the truth -as is stated even in Hamlet- there’s such a mistake that a word cannot be understood because it’s totally misspelled, even so that the word ‘tell’ can be found in the last line written correctly. So if ‘tell’ would be the intended word then there are two errors (missing initial letter, lost second l), but the situation is the same when we accept the spell version: a missing second letter and a lost last l.

It’s hard to believe – of course possible, yet.

Hank, just look at the Preface to the First Folio, the next lines:

170: And ioy’d to weare the dressing of his lines!

171: Which were so richly spun, and wouen so fit,

Dressing the lines…woven so fit… Maybe who wrote it, did know something.

Whittemore, talking on Troilus and Cressida, I had the desire to read “A Lover’s Complaint” again. A couple of hours I took to read the 329 verses that some said to be wrote by Shakespeare.

I believe that it was wrote by Oxford. I believe too that the woman that tells her story is Queen Elizabeth talking on her affair with Oxford. Here, Oxford makes himself a villain and Elizabeth a victim of his lust, falsehood and youth. In “Venus and Adonis”, this story is exactly the opposite, where Elizabeth is almost a raper of the young Adonis (Oxford).

But reading the poem again, I found that the wooer of the woman that tells the story had many affairs before, many other bastards with differente women and he even said one of his lovers turn herself into a nun after fall in love with him and rejected many wooers. Now I’m divide between Elizabeth and Vavasour as the female narrator.

We could say Elizabeth was this nun. She call herself a virgin (tough she was not such) and rejected many suitors (this is a historical fact that even changed the History of England forever). She make Oxford her favorite and had an affair with him between 1573-1575. Yet, Vavasour was Oxford’ mistress too and, like the last verse says, she was a Maid (of Honour of the Queen). Oxford was her first lover to whom she must have lost her chastity, like the narrator of “A Lover’s Complaint”.

Even though, the narrator says that she gave to her wooer “all her flower”. As a PT Theoryist, this is a clear reference to Henry Wriothesley for this “flower” must be the same “purple flower” from “Venus ando Adonis”. This make the narrator the Queen herself.

Whittemore, I’m very confuse. Can you help?

Francisco, I think it’s quite possible that Oxford conflated two (or more) individuals to come up with some of his characters. In the case of A Lover’s Complaint, it’s confusing. On the one hand I’d say that it’s the Queen all through. On the other hand, it is interesting that A Lover’s Complaint has the same “echo” format that Oxford’s own “echo” poem has — and Spenser, too. I have always been suspicious of Vavasour being the object of Oxford’s echo poem. It’s possible, even though the “nun” in that poem must be the Queen: “I might discern her face,/ As one might see a damask rose hid under crystal glass.” Sounds like the Tudor Rose, all right.

In the context of the book of sonnets, A Lover’s Complaint is positioned much like the Bath Sonnets at the end 153-154, which serve actually as prologue — and the Complaint is early, too. It is unmistakable the young Oxford and the Queen, and helps fill in the foreground of the sonnet story.

That’s the most confusing part of “A Lover’s Complaint”. To be united to this sonnets, right in the end of the Dark Lady’s Sonnets, could sugest that Elizabeth was the “Lover”. If Oxford was or not the author, he was certainly the young and lustful wooer of this story.

Are you speaking of the poem “Anne Vavasour’s echo”? If yes, is very probable that Oxford wrote it and make it one of his early poems with the anagram of his last name, Vere as Ever.

Could Oxford, or the true author of “A Lover’s Complatin”, using Vavasour’s voice to talk on Oxford affair with Elizabeth by refering her as “a nun”. But the Lover says that she “gave him all my flower”. I’m following Percy Allen’s logic in that Elizabeth was the Lover, the wooer Oxford and the flower was Willie Hughes (he made his PT Theoryist analysis before he changed his ideias of Hughes to the more logic Southampton).

Then, the “flower” was a reference to the Tudor Rose and in this context, is Hughes/Southampton himself. Is impossible to Vavasour have been Southampton’s mother. Here is the cause of my confusion. Vavasour and Oxford had the bastard Edward Vere, so he hadn’t royal blood. As a follower of PT Theory Part II, maybe Edward Vere had royal blood by his father, Elizabeth’s first born.

But you don’t believe in Pt Theory Part II.

But let know thinking twice: Elizabeth wasn’t, in fact, the only nun. The Maids of Honour of the Queen couldn’t have sexual relationships and couldn’t marry without their Queen’s permition. Mary Fitton, Elizabeth Vernon and Vavasour herself are example of the consequences of breaking this rule: they and their lovers ended up in jail.

Yet, by the time of Elizabeth’s and Oxford’s affair started, Anne Cecil, his wife, didn’t had children. The Lover of the poems said to know that her wooer had children of other women. When Oxford’s affair with Vavasour started, in 1580, he had already children by his ex-wife and mistress. But where is the son of royal blood (“flower”) that Vavasour could bare to Oxford?

There’s such a confusion in my mind.

Francisco, I do believe that PT II may well be correct. But believe that it must be correct that Southampton was Oxford’s first-born son. And that Southampton was also his son by the Queen. I have focused on the Sonnets, primarily, because that has seemed a large-enough task.

I must consult the Complaint again for the line or lines about the male having had children of other women. Which lines are they?

Hi Hank,

I’m terribly sorry, I was completely mistaken about sonnet 76.

No, it’s not FELL.

My friend, it’s crystal clear now to me: it’s SEL(L). The very same SELL, which is the last word in sonnet 21:

‘I will not praise that purpose not to sell.’

Back when I read your explanation in The Monument, I can remember, I didn’t quite find it a Shakespearean-quality line, him explaining to Southampton that he’s not going to sell (for money, like a simple monger, etc.) these private sonnets.

But now in my vocabulary I’ve found the perfect meaning of sell for us: to uncover/disclose the truth or a secret.

And suddenly both sonnet 21 AND sonnet 76 gains a new meaning at some places: in 21 Oxford would promise that though he’s praising Henry (knowing the REAL truth, while others say what they want from just hear-say), but his purpose is NOT to reveal Henry’s identity – NOT TO SELL HIS TRUTH.

And in 76:

‘That every word doth almost sel(l) my name’

that is almost every word reveal the secret, that he is Oxford, writing about the Queen and his son. One almost can see the act of revealing by someone, showing to the enemy one’s hiding place, or:

‘Showing their birth, and where they did proceed’

What do you think of this?

Whittemore, is Stanza 21, I think. It’s says:

“‘So many have, that never touch’d his hand,

Sweetly suppos’d them mistress of his heart.

My woeful self, that did in freedom stand,

And was my own fee-simple, not in part,

What with his art in youth, and youth in art,

Threw my affections in his charmed power,

Reserved the stalk and gave him all my flower.”

I think it’s stanza 25:

“For further I could say this man’s untrue,

And knew the patterns of his foul beguiling,

Heard where his plants in others’ orchards grew…”

That’s about as close I can get, so far. But it’s surely ambivalent or unclear — she seems to be talking about rumors, gossip, what she has heard. I don’t think it’s intended that we think the wooing young man has actually fathered children.

“Gave him all my flower” might refer to the purple flower of Venus and Adonis, or to the little western flower of A Midsummer’s Night Dream — i.e., to Southampton — but I had understood it here as only referring to her being deflowered, sexually.

Step by step in this coversantion, I’m getting clear that the Queen was the Lover. In the poem, the Lover says too that her wooer wooed her since their very young age. Elizabeth’s relationship with Oxford before he was made her ward was like a mother and a son, bonded in blood. Oxford knew his Queen well since his most young age and maybe the love poems he wrote during his young age were to Elizabeth. Could Oxford fall in love with his own mother since such a young age?

Yet, who could have been the nun which rejected many wooers for the wooer who later broke her heart? Did Oxford penned “A Lover’s Complaint” making Elizabeth the narrator but dividing her into two characters?

We have the broken-hearted Elizabeth telling her story and then, she talks on herself but like she was not her. Is the unchaste Elizabeth talking on the chast (nun) Elizabeth, because she (which was no longer virgin) should be so and Oxford’s lust and youth didn’t help her in this problem.

Could this be the truth behind the Lover and the Nun?

The confusion is bigger now 😛

In the first stanzas of the poem, the Lover, called by the poet as “the carcass of a beauty spent and done”, tells to the old man she isn’t so old as she looks and she even compare herself in youth to a flower.

Was this flower a early reference in the poem to the Tudor Rose?

Elizabeth was 40 years old in 1573, when her affair with Oxford must have started. In 1575, when the affair broken up, she was 42 years old and in 1581, when Oxford had Vavasour has his new mistress, the Queen was 47 years old.

Vavasour was 21 or 20 years old in this time.

Yet, we can look at the last distich of the poem and we shall find the Lover saying:

“Would yet again betray the fore-betray’d,

And new pervert a reconciled maid!”

Could the “reconciled maid” be a reference to Vavasour as a Maid of Honour of the Queen and she is “reconciled” for she betray her mistress’ trust and rules?