[Following is my talk at the Shakespearean Authorship Trust (S.A.T.) conference at Shakespeare’s Globe in London on 24 November 2019. The text has been adjusted for print and slightly expanded for greater clarity.]

Some years ago, I was on a train heading down to New York City and found myself sitting next to a distinguished looking gentleman who turned out to be an architect who also loved literature and drama. We began talking and he asked me about myself and, at some point, I mentioned I’m one of those folks looking for the “real” Shakespeare. He turned and looked at me with intensity and put up his finger, and I flinched. Who knows what this topic is going to bring out in people!

“Look,” he said, “there are two things you have to know about Shakespeare, whoever he was. One, he uses words to stimulate the muscle of your visual cortex, so it throws images on the screen of your mind.” He mentioned some examples, such as Horatio in Hamlet describing the dawn as a knight in rusted armour, climbing up “o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill.”

“The second thing you need to know,” he said, “is that Shakespeare is a storyteller. And his greatest stories are tragic. Therefore, just identifying the real author will not be good enough. What you need to do is find that tragic story.”

We talked a lot more … the authorship question was new for him and he thought the whole idea of this mystery must be deeply sad and tragic. He was thinking about how this great author’s identity could have been obliterated. He considered it would have been a form of murder, or suicide, in the face of some powerful force against him.

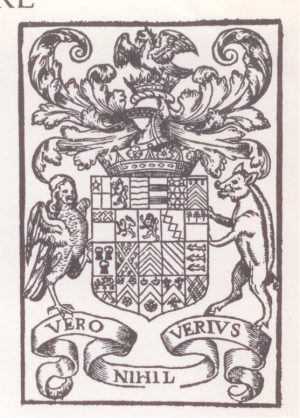

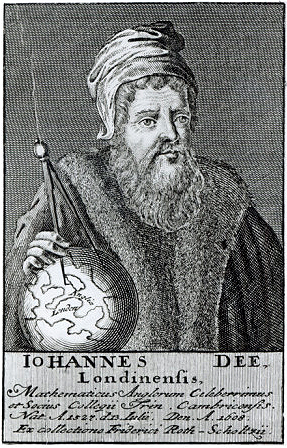

Edward de Vere

17th Earl of Oxford

Well, as many of you know, I’m convinced the true voice of the author is that of Edward de Vere, Lord Oxford, and that he provided the unifying vision of the individual artist that we know as “Shakespeare.” And, too, that it’s in the Sonnets where we find his most directly personal voice.

Oxford’s death or disappearance in June 1604 was followed soon upon by publication of the full-length second quarto of Hamlet; and in that great tragedy, the protagonist, the most autobiographical of all Shakespearean characters, cries out to his friend: “O God, Horatio, what a wounded name! Things standing thus unknown shall I leave behind me!” Then he begs Horatio to “tell my story” — his tragic story that remains unknown to the world; and that sounds like what my friend on the train was talking about.

Well, the focus of our gathering here at Shakespeare’s Globe is the failed Essex Rebellion led by the earls of Essex and Southampton – an event which, I submit, is the inciting incident of the tragic story of the Shakespearean author’s posthumous loss of identity. In this view the rebellion is not the end of the story, but, rather, the beginning of de Vere’s final evaporation behind the pen name; and this perspective sheds light on a crucial legal story that I want to share with you.

I also hope to show that Oxford countered this loss of identity with a super-human effort to create, in the Sonnets, his final masterwork – to preserve his final story and prevail in death, thereby creating his own resurrection and ultimate triumph.

This final story takes place during the two years and two months following the failure of the so-called rebellion — a period which, I suggest, is the true historical time frame and all-important context for Oxford’s posthumous disappearance as the author. This was a dark time when Southampton languished in the Tower as a convicted traitor; when the condemned Earl of Essex wrote a long poem to Queen Elizabeth from his prison room, during the four days before his execution; and when Southampton also wrote a long poem to her Majesty from his Tower room, begging for mercy – a poem discovered less than a decade ago. (“Was Southampton a Poet? A Verse Letter to Queen Elizabeth” by Lara M. Crowley, English Literary Renaissance, 2011.)

I agree with Ms. Crowley that these poems by the earls are more accurately called “verse letters” of communication with the queen; and clearly the Sonnets are verse letters as well.

First the prologue: the Shakespeare pseudonym making its grand entrance just eight years before the rebellion, in 1593, when things are heating up to determine control of succession to Elizabeth – who, by refusing to name anyone, is putting the country in danger of civil war around the throne when she dies. The Essex faction is up against the entrenched power of William Cecil Lord Burghley and his rapidly rising son Robert Cecil, the cunning hunchback seething with resentment toward those nobles whom he views as so unfairly fortunate by their birth alone. The goal of the Essex faction is to prevent the Cecils from continuing their power into the next reign; but I don’t need to tell you that Robert Cecil is going to win this game. He is going to outwit and outmaneuver those spoiled, arrogant noblemen.

(Consider this strikingly blunt comment about Robert Cecil from the Dictionary of National Biography 1885-1900: “Life was to him a game which he was playing for high stakes, and men and women were only pieces upon the board, set there to be swept off by one side or the other or allowed to stand so long only as the risk of letting them remain there was not too great.”)

Now in 1593 the previously unknown author William Shakespeare (without any prior history of written work) suddenly appears on the dedication of Venus and Adonis to Southampton. “Shakespeare” is on the side of those same young lords heading toward their tragic end game, which is also the end game to determine the future course of England.

A year later, in the 1594 dedication of Lucrece to Southampton, the same author confirms where he stands with an extraordinary public promise: “The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end …What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours.” This from a great author with a vast storehouse of 25,000 words from which he can choose, who never needs to repeat any word twice, much less three times in a single sentence.

It’s a pen name, saying, in effect: “All the writings I have done so far (i.e., the two narrative poems), and all the writings I am going to do in the future, published under this name, are for you and in your support. These written works are, and will be, yours … yours … yours.”

Once Burghley dies in 1598 and Principal Secretary Cecil takes over, the gloves come off with the first issuance of plays under the pseudonym, among them Richard III with “Shake-speare” hyphenated as if to emphasize the image of a writer “shaking the spear” of his pen. This play of royal history contains a mirror image of the hunchbacked Cecil, an allegorical portrait of him as an evil monster, and a shockingly obvious attack on him that the secretary cannot, will not, ever forgive. He will bide his time, keeping a steady course, until he gets revenge.

In the next year, 1599, it appears that “Shakespeare” in the chorus of Henry V is publicly cheering for Essex’s success on the Irish military campaign, in which Southampton is also a leader. The playwright predicts that “the general of our gracious Empress” will return with “rebellion broached on his sword,” but the effort to crush the revolt is doomed – in no small part because Cecil has prevented the earls from receiving the needed assistance.

That fall back in London, Essex is in deep trouble with the queen and her council, under Cecil’s pressure against him. Meanwhile Southampton spends much of his time attending politically instructive plays at the Curtain such as Julius Caesar by “Shakespeare,” who, for the public audience, is creating an allegorical road map toward avoiding civil war and achieving a peaceful royal succession.

Queen Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603)

Events are moving fast, tensions are building, as the aging queen falls increasingly under Cecil’s influence. In January 1601 Southampton is attacked in the street by Lord Gray and his party on behalf of Cecil and Raleigh; the earl draws his sword and fights them off with the help of his houseboy, who joins in the fray and has one of his hands lopped off. As far as Essex and Southampton are concerned, they are in mortal danger and can no longer delay taking action.

In the first week of February, Southampton takes charge of planning to finally gain access to the queen at Whitehall. They plot to hold Cecil captive so Essex and Southampton can be in her Majesty’s presence and convince her to call a Parliament on succession – to finally name someone, even give up her crown, avoid civil war, and remove Cecil in the bargain.

Preparing for this confrontation with the queen, the conspirators on Sunday 7 February 1601 attend a special performance of Richard II with a deposition scene of the king handing over his crown. In this newly revised play, Oxford demonstrates to the Essex faction how it might be possible to confront Elizabeth with rational arguments and persuade her to do the same – without, most importantly, violating the laws of God or man.

Of course, the play is viewed allegorically, making it easy for Cecil to incite the queen’s fear and anger; and Elizabeth well understood, as she later exclaimed: “I am Richard Second, know ye not that!”

More immediately, however, the cunning Cecil uses this special performance to summon Essex to the palace that night for questioning; and his calculated move predictably causes the earl to panic. The next morning, at Essex House, his followers are clamoring in the courtyard amid an atmosphere of chaos. The subsequent events predictably end in disaster; that night, both Essex and Southampton surrender up their swords and are taken through Traitors Gate into the Tower of London, facing charges of high treason against the crown and virtually certain execution.

Eleven days later, at their joint trial in Westminster Hall, are two of the future leading candidates for the authorship of the “Shakespeare” works: Sir Francis Bacon, viciously prosecuting; and Lord Oxford, having come out of retirement to sit as highest ranking earl on the tribunal of peers sitting in judgment. The accused earls will both be found guilty and sentenced to death; Essex will be executed six days later, but Southampton will find himself in perpetual confinement.

Now all authorized publications of as-yet-unprinted Shakespeare plays have abruptly ceased; aside from the full Hamlet in 1604, there will be no more newly printed authorized plays for nearly two decades; but my theme here is that the rebellion is not the end of author’s tragic story, it’s the beginning.

Southampton in the Tower: 8 February 1601 – 10 April 1603

In the normal telling it’s the conclusion: Southampton remains in the Tower while Cecil, under terrible tension, works desperately and even treasonously to communicate in secret with King James in Scotland. In that traditional history, Shakespeare writes few if any sonnets to Southampton all during the twenty-six months of his imprisonment. Then, upon Henry Wriothesley’s release from the Tower by King James on 10 April 1603, the author suddenly exclaims in Sonnet 107 that “my true love” had been “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom” but is now free; and, therefore, “my love looks fresh” – once again, offering the young earl his endless love, devotion and commitment.

Was Shakespeare a hypocrite? His true love in the prison and he writes maybe a few private sonnets to or about him, or none at all, only to jump back on the bandwagon when Southampton is liberated? Well, I don’t think he could have been hypocritical.

Thinking about my friend on the train describing Shakespeare as a masterful storyteller, I recall the diagram of the most basic structure of a story, the way my English teacher drew it on the blackboard. In that light, if Sonnet 107 at the climax celebrates Southampton getting out of the Tower, in 1603, how could we care about that event unless the author has already established when he was put in the Tower two years earlier, back in 1601? In the framework of such a story, certainly Southampton’s entrance into the prison fortress is the inciting incident that finally reaches the climactic turning point later, in 1603.

Why would we care about Southampton getting out of the Tower if we didn’t know, in the first place, that he was in there? Well, if we climb back down the consecutively numbered sonnets, we can see that the usual view is wrong. A journey “back down the ladder” of sonnets takes us through a long series of darkness, despair, prison, trial, legal words related to crime, guilt, death – all the way back down to where this great wave of darkness and suffering first appears; and then it becomes clear that literally dozens and dozens of sonnets have been leading up to the climax.

The author did not abandon Southampton; he never stopped writing to or about him; and in this context – the context of the prison years – those legal words are no longer metaphorical; rather, they are real, and carefully accurate: real words applied to real life, when the author is steeling himself against the worst outcome for the young earl.

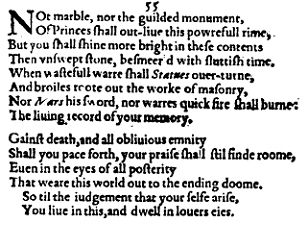

Now I hope you’ll to indulge me for less than ninety seconds, as we take a quick “fly-over” to view these words from the high point of Sonnet 107 back downward; and this is just a sampling of those dark and legal words as we climb back down to where they begin at Sonnet 27:

(Sonnets 106-96): Confined doom, Wasted time, weak, mournful, despair, death, dark days, decease, fault;

(Sonnets 92-87): Term of life, thy revolt, sorrow, woe, fault, offence, night, attainted, misprision, judgment;

(Sonnets 86-77): Tomb, dead, confine, immured, attaint, decayed, waste, graves; (74-66): Fell arrest, bail, death, buried, blamed, suspect, died, dead, for restful death I cry;

(Sonnets 65-57): Plea, gates of steel, drained his blood, shadows, for thee watch I, imprisoned, pardon, crime, watch the clock for you;

(Sonnets 55-51): Death, judgment, die, deaths, shadows, shadow, up-locked, imprisoned, offence, excuse;

(Sonnets 50-46): Heavy, bloody, grief, lawful reasons, allege, bars, locked up, thyself away, defendant, plea deny, verdict;

(Sonnets 43-38): Shadow, grief, waiting, blame, forgive, grief, absence, torment, pain;

(Sonnets 37-33): Shadow, confess, guilt, trespass, fault, lawful plea, offender’s sorrow, ransom, basest clouds;

(Sonnets 32-27): If thou survive, dead, grieve, buried, death’s dateless night, disgrace, outcast, hung in ghastly night…

That’s just a sampling of the “dark” words and legal terminology in the eighty sonnets from the climax of Sonnet 107 all the way back down to number 27, in which the author tries to sleep that night in the darkness, but his mind travels instead to Southampton in the Tower. He can imagine the earl up there in a window, like “a jewel hung in ghastly night.” In the dictionary “ghastly” is “frightful, dreadful, horrible,” as in “a ghastly murder” – or, we can be sure, like the ghastly torture of being hanged, drawn and quartered.

SONNET 27 on the night of the failed Rebellion on the Eighth of February 1601, where the story begins:

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travail tired.

But then begins a journey in my head,

To work my mind, when body’s work’s expired.

For then my thoughts (from far where I abide),

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness, which the blind do see.

Save that my soul’s imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which like a jewel (hung in ghastly night)

Makes black night beauteous and her old face new.

Lo thus by day my limbs, by night my mind,

For thee, and for myself, no quiet find.

Southampton entering the Tower as a prisoner is the first of many recorded, factual events. The overall circumstance is that he’s accused of a crime; and sure enough, in this diary of verse letters, Oxford calls it by name:

“To you it doth belong yourself to pardon of self-doing crime” – Sonnet 58

“How much I suffered in your crime.” – Sonnet 120

In this case, the crime is that of treason, the most serious offence Southampton could have committed. It would almost cost him his life and cause the author of the Sonnets to descend into darkness and despair and finally to disappear. So, now, from Sonnet 27 forward, we have what might be called the “foundational tracks” of his personal story. These tracks during Southampton’s more than two years in prison are on the record; Oxford knows they are events that will be indelibly stamped upon English history.

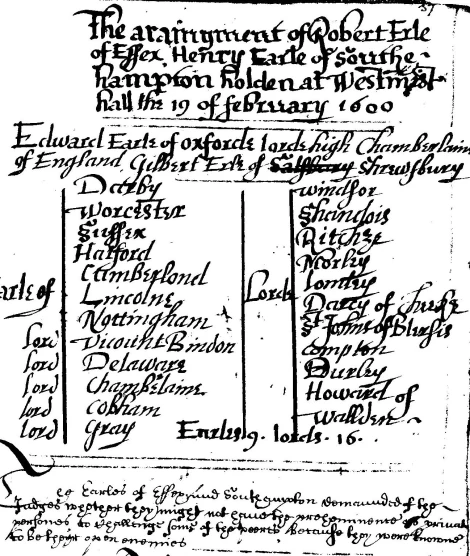

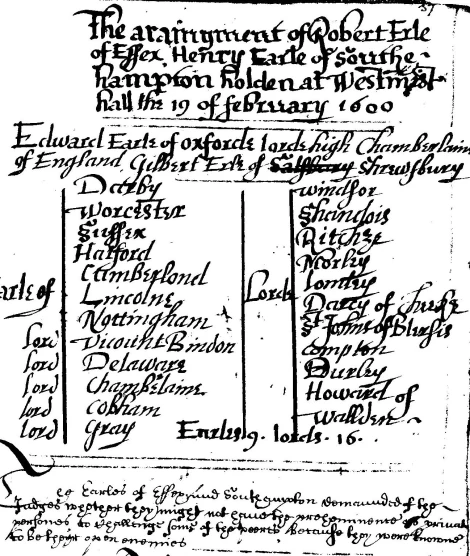

Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford served as highest-ranking nobleman on the tribunal at the February 19, 1601 treason trial of Essex and Southampton — as indicated by a contemporary notice of the event

FEBRUARY 11, 1601: The twenty-five peers, Oxford among them, are “summoned” to serve on the tribunal at the “sessions” or treason trial; and in Sonnet 30 the author writes: “When to the Sessions of sweet silent thought, I summon up remembrance of things past.” Yes, it’s poetry, but I suggest there’s a “second intention,” which is actually the primary context – and, as you have probably noticed, that’s the most important word of this talk: context.

FEBRUARY 19, 1601: The trial of Essex and Southampton is held on this day at Westminster Hall. Bacon prosecutes; Oxford sits with the peers, who come to a foregone unanimous conclusion: both earls are found guilty of treason and sentenced to be executed.

Oxford, reacting to the tragedy, addresses Southampton in Sonnet 38 and wonders in sorrow: “How can my Muse want subject to invent/ While thou dost breathe? … The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise.” In Sonnet 46 he glances back at the recent trial: “And by their verdict is determined…”

FEBRUARY 25, 1601: Essex is executed on the Tower Green by beheading; and the poet writes in Sonnet 44, referring to Southampton and himself, about their “heavy tears, badges of either’s woe.”

MARCH 5, 1601: The treason trial of five conspirators; all convicted and condemned to death; and Oxford writes to Southampton in Sonnet 57: “I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you.”

MARCH 13, 1601: Gelly Merrick & Henry Cuffe are hanged, drawn and quartered. “For thee watch I,” Oxford writes to Southampton in Sonnet 61; and in Sonnet 63 he sets down his fears that Wriothesley will face the executioner’s axe – using a double image that combines both universal time/age and specific words such as “knife” and “cut” and “life” related to beheading:

For such a time do I now fortify

Against confounding Age’s cruel knife,

That he shall never cut from memory

My sweet love’s beauty, though my lover’s life.

MARCH 18, 1601: Charles Danvers & Christopher Blount are publicly beheaded, leaving Southampton as the only one with the death sentence hanging over him; and the author writes Sonnet 66 as a virtual suicide note, listing reasons he wishes to die:

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry …

Tired with all these, from these I would be gone,

Save that to die, I leave my love alone.

He would prefer to kill himself, but will not commit suicide while Southampton remains alive and “alone” in the Tower. In that same virtual suicide note, he complains about “strength by limping sway disabled,” and John Dover Wilson (in his Cambridge edition of the Sonnets in 1969) finds it “tempting to suspect a glance at the control of the state by the limping Robert Cecil.” Well, as my friend on the train might say, it’s not only tempting, it “stimulates the muscle of our visual cortex” to create an image of Cecil swaying and limping toward his “disabling” or destruction of the earls.

“And captive good attending Captain Ill,” Oxford adds. Southampton, the captive prisoner, is at the mercy of Captain Ill, echoing Cecil, the captain in command of the situation.

Early the next morning, crowds wait on Tower Hill for the spectacle of Southampton being executed, but they’re disappointed because, without official explanation, the scaffold is taken down. The earl’s life has been spared. His sentence is quietly reduced to perpetual confinement. He becomes a nobody, stripped of all lands and titles, and is now “Mr. Henry Wriothesley,” a commoner, and even “the late earl” – a dead man in the eyes of the law; and therefore, in Sonnet 67: “Ah, wherefore with infection should he live … Why should he live …?” And in Sonnet 69: “Thou dost common grow…”

Is Cecil is holding him hostage in the Tower? If so, the key must be Oxford himself and Cecil’s need to remove all future trace of him as the author calling himself Shakespeare, the poet-dramatist who devoted his work to Southampton, and, too, who had depicted Cecil as the monstrous ruler Richard the Third.

In number 87 of this diary of verse letters, Oxford supplies the legal mechanism by which Southampton’s life was spared:

So thy great gift, upon misprision growing,

Comes home again, on better judgment making

“Misprision of Treason” is literally a “better judgment” or verdict, a reduction of the crime of treason. This special judgment is a kind of plea bargain, used by Tudor monarchs to gain information in exchange for a lesser verdict. It means Southampton was supposedly ignorant of the law; he knew about the plot but didn’t really participate and failed to report it; he expresses true sorrow or repentance; and it gives him the possibility of future liberation and even a royal pardon, so he cannot be retried for the same offence.

Oxford supplies a crucial account of how this better legal judgment for Southampton was obtained. Soon after Sonnet 27 on the night of the failed rebellion, anticipating the trial, he promises Southampton in Sonnet 35 that “Thy adverse party is thy Advocate,” or as editor Katherine Duncan-Jones reads the line: “Your legal opponent is also your legal defender.”

Oxford has no choice but to join the other peers on the tribunal, in effect acting as Southampton’s “adverse party,” forced to vote with them to condemn him to death; but he also vows to work (privately, behind the scenes) as the earl’s “Advocate” or defense attorney, trying to save his life.

He must make a deal with Cecil, his former brother-in-law; and as he records in the Sonnets, there is a kind of prisoner exchange, that is, Oxford offers his life in exchange for Southampton’s reprieve from execution and possible future liberation. The younger earl is in fact spared from execution, without any official word, but he must remain in confinement until the monarch decides to release him and perhaps grant him a pardon.

Oxford instructs him on the law (and the plea deal), adding in Sonnet 58, “To you it doth belong yourself to pardon of self-doing crime,” that is, “Your life is in your own hands, young man.”

The monarch who may give him a pardon, however, will not be Elizabeth, who is much too angry and fearful. Cecil must succeed in bringing James to the English throne; only then will Cecil can he continue in his position of power, and only then might Southampton get out alive. Therefore, to save Southampton, Oxford must agree to help Cecil make James the King of England. (And to that end, perhaps Edward de Vere is the unidentified “40” in the Secretary’s secret correspondence with the Scottish king).

Also in Sonnet 35, Oxford blames himself for “authorizing” the crime as author of Richard II and depicting Elizabeth “with compare” as that historical king; as Duncan-Jones explains, “authorizing” is “used here in a legal sense for sanctioning or justifying, with a further play on ‘author’ as composer or writer.”

All men make faults, and even I in this,

Authorizing thy trespass with compare…

Oxford is guilty not only for writing Richard II with its deposition scene, but, also, for allowing the Chamberlain’s Men to give the special performance of his play that Cecil then used to trigger the whole debacle. The actors are called in for questioning, but not the author, even though he had played a crucial role in the crime. In fact, he himself could possibly be charged with Treason by Words, if the queen chose to believe that Richard II depicts her as a tyrant. Oxford, too, could be executed.

More important to Cecil, however, was being able to ensure that Oxford, his former brother-in-law, could not be linked to the portrait of him in Richard Third (or, for example, that Oxford could not be linked to portraits of Burghley in the quartos of Hamlet). Instead of Oxford himself being physically executed, his identity could be obliterated beyond his death — forever — behind the Shakespeare pen name. Oxford could agree to that (and to ensuring that no one who know the truth will ever reveal it), if it means saving Southampton; and therefore, an essential part of the plea deal is his self-sacrifice.

In Sonnet 35 he records his acceptance of posthumous disappearance: “And ‘gainst myself a lawful plea commence” – a legal plea bargain, directed against himself. At the same time, Southampton must agree to his own guilt and confess that he never meant to commit treason; and so, for example, he writes to the Privy Council from his prison room: “My soul is heavy and troubled for my offences … My heart was free from any pre-meditate treason against my sovereign….”

Oxford refers in Sonnet 34 to the younger earl’s need to repent, while he himself must take on a Christlike role:

Though thou repent yet I have still the loss,

The offender’s sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offence’s cross …

In his poem to the queen, Southampton begs for mercy:

Vouchsafe unto me, and be moved by my groans,

For my tears have already worn these stones.

His tears of repentance are “riches” to be paid, the way other noble prisoners are able to use actual money to purchase their freedom. Oxford reminds him in Sonnet 34 that his tears of repentance are a form of “ransom” for his life and possible liberty:

Ah but those tears are pearl which thy love sheeds (sheds),

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

The price also includes total separation from each other – in life, on the record, in future history. Oxford had linked Southampton to the pen name; the earl and the famous pseudonym went together; therefore, now Oxford must agree to de-link himself from not only “Shakespeare,” but, also, from Southampton. The two of them must be “twain” or apart, one from the other, as Oxford tells Southampton in Sonnet 36:

Let me confess that we two must be twain …

I may not ever-more acknowledge thee…

The author, a legal expert, finds in Sonnet 49 another way to phrase the same legal bargain behind the scenes:

And this my hand against myself uprear,

To guard the lawful reasons on thy part.

To leave poor me, thou hast the strength of laws…

The dark time continues, no one knowing the outcome.

FEBRUARY 8, 1602: First anniversary of the failed Rebellion: Southampton has spent one full year in prison, as Oxford records in Sonnet 97:

How like a winter hath my absence been

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year!

“Fleeting” is a deliberate play on the Fleet Prison to emphasize Southampton’s continuing confinement.

FEBRUARY 8, 1603: Second anniversary, marking two years or “three winters cold” in the Tower as indicated in Sonnet 104, covering the three Februaries of 1601, 1602 and 1603.

MARCH 24, 1603: Queen Elizabeth, the “mortal Moon,” dies in her sleep and those “sad Augurs” who predicted civil war are proved wrong. Cecil quickly proclaims King James of Scotland as James I of England, and the new monarch, who uses “Olives” to symbolize peace, quickly sends ahead the order for Southampton’s release. On April 10, 1603, after all the uncertainties are crowned with assurance, and after Southampton was “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom,” he walks out of the Tower as a free man and Oxford records this amazing climax of his recorded story in Sonnet 107:

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul

Of the wide world dreaming on things to come

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Supposed as forfeit to a confined doom!

The mortal Moon hath her eclipse endured,

And the sad Augurs mock their own presage,

Incertainties now crown themselves assured,

And peace proclaims Olives of endless age.

Now with the drops of this most balmy time,

My love looks fresh, and death to me subscribes,

Since ‘spite of him I’ll live in this poor rhyme,

While he insults o’er dull and speechless tribes.

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent.

How very confident de Vere is that these “verse letters” are going to comprise a “monument” for Southampton that will outlive the crests of tyrants and the brass tombs of kings! As Oxford promised him in Sonnet 81:

Your monument shall be my gentle verse,

Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read…

And now, proceeding from the climax of number 107, the story’s resolution unfolds in nineteen days covered by exactly nineteen sonnets, advancing with increasing power and grandeur to the funeral procession bearing the coffin and effigy of Elizabeth under a canopy, on April 28, 1603, marked by Sonnet 125, the official end of the Tudor dynasty, followed immediately by the author’s envoy of farewell to “Oh thou my lovely Boy.”

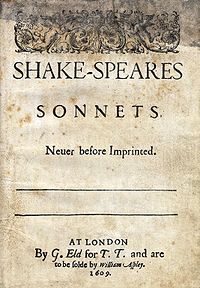

The result is a self-contained series of the 80 prison sonnets plus the 20 sonnets of resolution, exactly 100 sonnets or a “century” of them – mirroring Hekatompathia, or the Passionate Century of Love (1582), the 100 consecutively numbered sonnets attributed to Thomas Watson and dedicated to Oxford. The “century” within SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS is the central sequence of his monument for Southampton.

The younger earl will live on, but the author will disappear. Oxford consistently expresses this sacrifice of one life for the other — the exchange of his life or identity as “Shakespeare” for Southampton’s life as a free man:

When I, perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse. (Sonnet 71)

(When I am dead, you will continue without acknowledging me.)

My name be buried where my body is

And live no more to shame nor me nor you. (Sonnet 72)

(My identity will disappear, leaving you to flourish)

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die. (Sonnet 81)

(You are forever tied to “Shakespeare,” while I must disappear.)

In effect, these lines of the Sonnets comprise Edward de Vere’s own version of Hamlet’s cry for his wounded name. It’s a tragic story, but also the basic answer to the Shakespeare Authorship Question, delivered to posterity by the author himself — as he talks about his “poor name” or “name” to be “buried” and stating that he himself must die – not just in the physical sense, of course, but to “all the world.” He disconnects himself from “Shakespeare” and, therefore, from Southampton, ensuring that his own identity will disappear … but not forever!

In fact, Oxford is counting on these very sonnets to “tell my story,” as Hamlet begs his friend Horatio. Back in Sonnet 55, when Southampton’s fate was by no means certain, Oxford vowed to create “the living record of your memory,” adding:

’Gainst death and all-oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth! Your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

In this way he will triumph over Time and defeat the false “registers” or “records” upon which the future writers of history will rely. He himself will prevail in these sonnets, which will be printed in 1609 only to be quickly suppressed and driven underground, until the quarto’s reappearance more than a full century later. And so he defeats Time and Cecil and even Death, as expressed in Sonnet 107: “I’ll live in this poor rhyme.”

He draws his breath in pain, to tell his story. The “monument” of the Sonnets is his ultimate triumph, as expressed in Sonnet 123:

No! Time, thou shalt not boast that I do change!

Thy pyramids built up with newer might

To me are nothing novel, nothing strange:

They are but dressings of a former sight.

Our dates are brief, and therefore we admire

What thou dost foist upon us that is old,

And rather make them borne to our desire

Than think that we before have heard them told.

Thy registers and thee I both defy –

Not wond’ring at the present, nor the past,

For thy records and what we see doth lie,

Made more or less by thy continual haste.

This I do vow, and this shall ever be:

I will be true, despite thy scythe and thee.

/////